Over the past two weeks, I have had the opportunity to discuss AI and fundamental rights at two different, yet complementary, events: the 2nd meeting of the AI Act Correspondents Network, organised by the EDPS at the EU Parliament (see Wojciech Wiewiórowski’s blog post), and the EDEN Conference, organised by the Europol Data Protection Experts Network.

In both contexts, the importance of respecting fundamental rights when developing and using AI has been acknowledged. This reaffirms the EU’s approach to AI at a time when some have overlooked the fact that the protection of fundamental rights is at the core of EU digital technology regulation. This misconception stems from a confusion surrounding the relationship between law and economic interests (see Kuner’s recent comments on this).

While the legitimate concern about the cost of standing firm on our EU values should not be ignored, it is also crucial not to confuse the causes and remedies. The AI Act, like the GDPR, is not onerous simply because it protects fundamental rights. On the contrary, the approach they adopt is the best way to prevent or reduce litigation costs. In this respect, those who are against fundamental rights assessment (in its various forms) should recall that fundamental rights are protected at several levels in Europe, and the burden of risk assessment and mitigation is proportional to the risk introduced into society.

Neither the AI Act nor the GDPR has created fundamental rights. Rather, both acts simply implement specific procedures (assessments) to encourage a prior and by-design approach, which eases compliance and reduces the negative impacts of non-compliance in terms of reputation, compensation and sanctions. Therefore, it is clearly short-sighted to criticise fundamental rights impact assessments and similar instruments.

On the contrary, we must shift the focus from the debate on the provisions of the AI Act to their implementation. As I mentioned at the AI Act Correspondents Network meeting, public bodies and EU SMEs (which account for more than 90% of all businesses in Europe) are waiting for concrete tools to help them fulfil their obligations with respect to fundamental rights in the AI context. This is where the focus should lie.

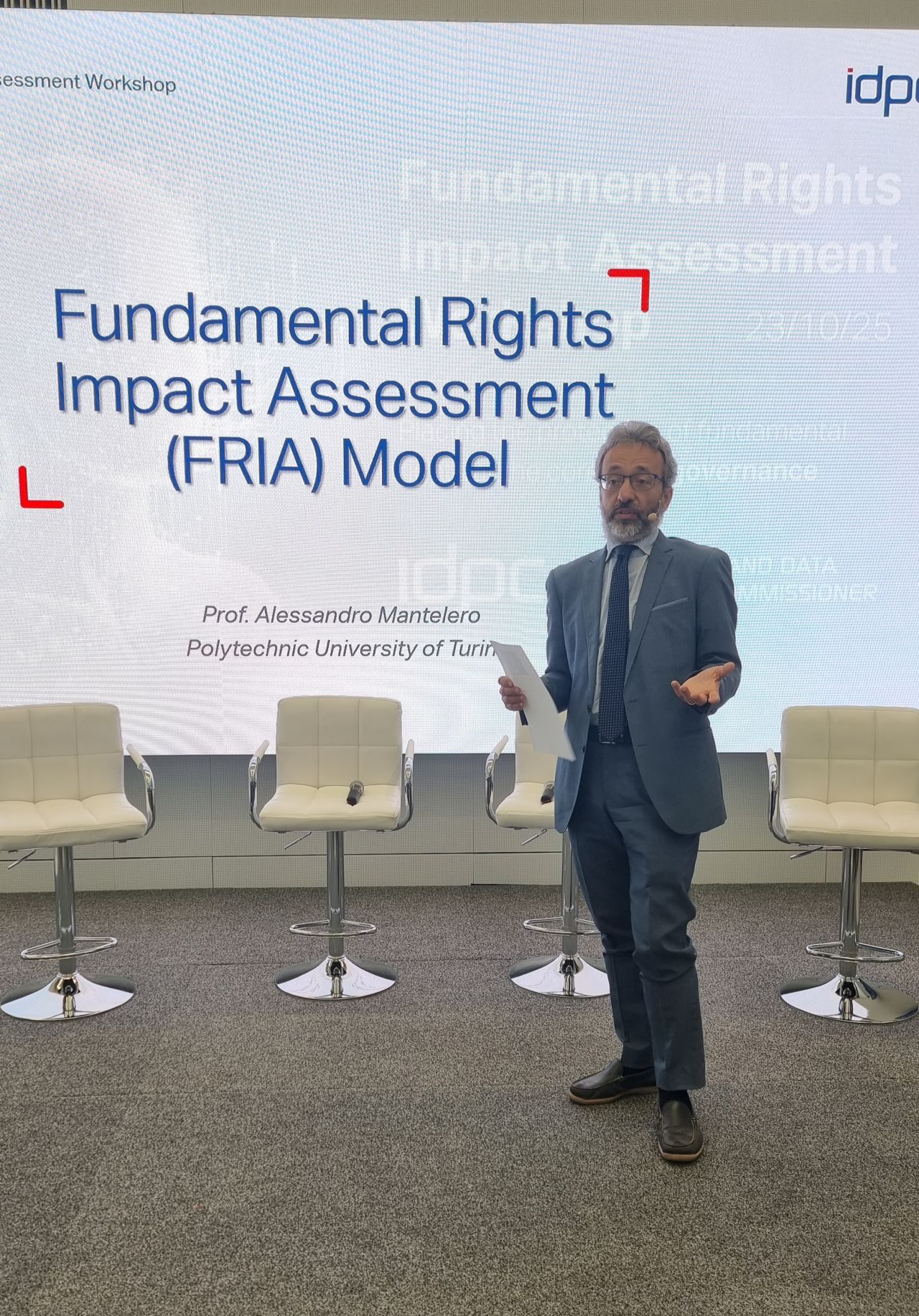

In this respect, the Information and Data Protection Commissioner (IDPC) in Malta organised a full-day workshop this week, focusing on Fundamental Rights Impact Assessment (FRIA) under the AI Act.

Together with over 80 experts from various fields, we used the Catalan FRIA model to demonstrate how to ensure compliance with fundamental rights when designing AI systems for real-world applications, while minimising the required effort.

The same scenario occurred the week before in Spain at the University of Murcia, where a similar workshop was organised in the context of the international conference From Algorithm to Patient, focusing on the health sector.

Based on my experience of these different fora and events, including a stimulating discussion with colleagues from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid at the conference on Ethical and Legal Perspectives on Advances in Artificial Intelligence, I think it is urgent to distinguish between the rhetoric of those who are lobbying for their industrial interests and the interests of EU citizens. For the latter, it is important that policymakers, industry and academia collaborate to develop trustworthy AI. This means, for instance, that AI solutions should not facilitate suicide or discrimination, nor should they be used to restrict rights.

This is possible if we focus more on ensuring legal compliance, providing adequate and easy-to-use tools to AI providers and deployers, rather than a misleading range of derogations that simply expose operators to litigation and persons and society to serious risks, contradicting the views and core interests of our cultures.