Last week, I was in Armenia as part of the EU delegation for the bilateral workshop on AI regulation, which was co-organised with the Ministry of High-Tech Industry of the Republic of Armenia. The aim of the workshop was to start a discussion about the current state of AI regulation in Armenia.

The workshop was chaired by H.E. Mr Vassilis Maragos, Ambassador and Head of the EU Delegation to Armenia, and introduced by Mr Ruben Simonyan, Deputy Minister of High-Tech Industry. During the same days, US Vice President J.D. Vance also visited Armenia, highlighting the strategic relevance of the region and the geopolitical dimension that regulation may also have (see Brasioli et al., The Routledge Handbook of Artificial Intelligence and International Relations, 2025).

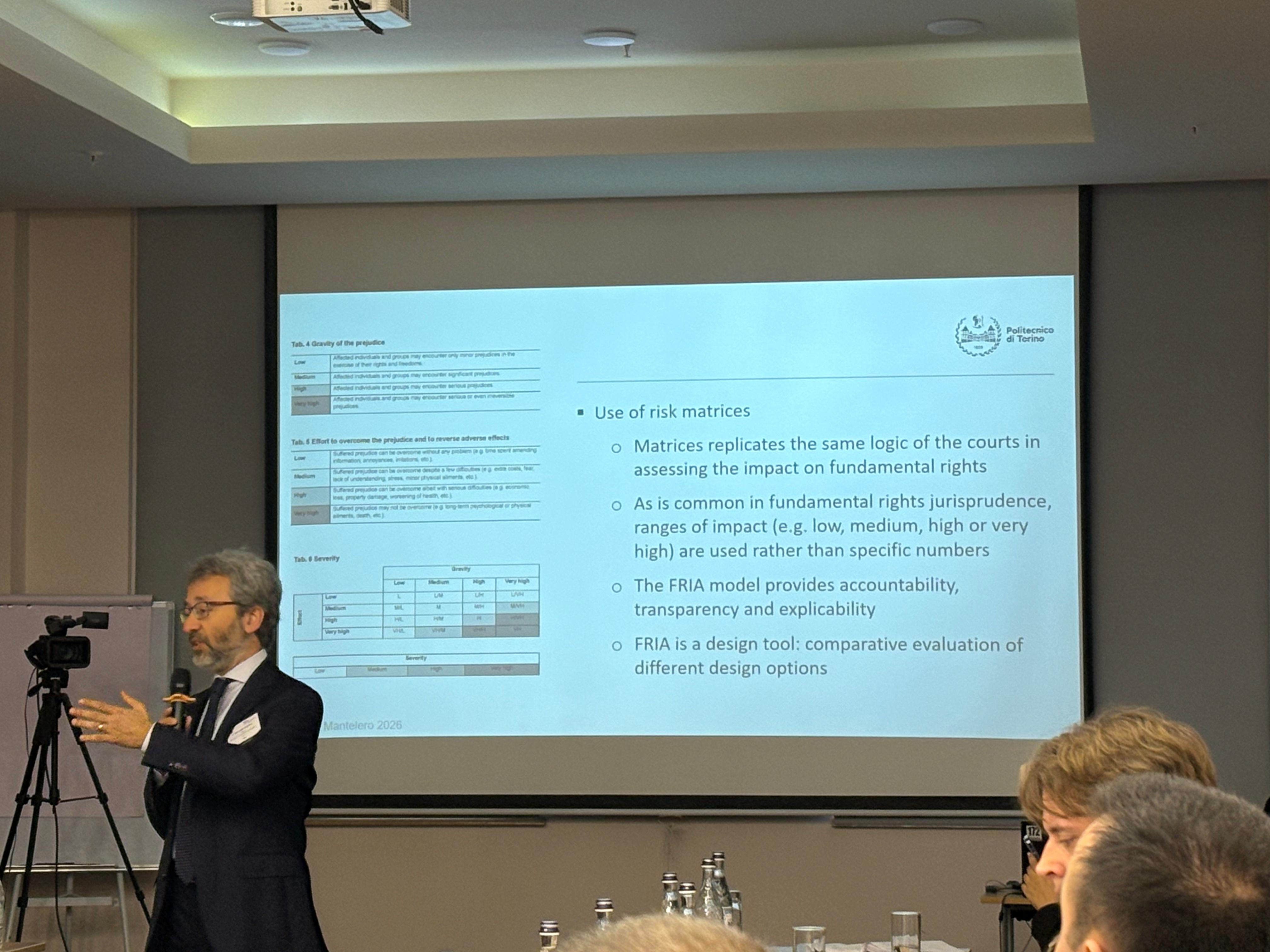

In my presentation on AI regulation, risk-based approach, fundamental rights impact assessment (FRIA), and disinformation, I pointed out how EU regulation could serve as a reference point while also being adapted to the specific Armenian context.

As I experienced in Brazil and other non-EU countries, the circulation of the EU model with regard to AI regulation is not based on the Brussels effect or a sort of neo-colonialist regulatory approach, but on common issues that different countries have to face. The challenges posed by AI to society, its potential risks, and the major role played by foreign companies – and, to some extent, foreign countries – find a potential response in the European regulatory approach, including the Council of Europe, in terms of value protection and the ability to combine innovation and safeguards.

While other countries may look to the EU AI Act and the DSA as possible models for drafting their national laws in this field, it is crucial to avoid a mere copy-and-paste approach. The circulation of legal models is not just replication, but a much more complex process of adaptation and integration. From this perspective, the complex governance set out in the AI Act can be simplified in the context of a national state. On the other hand, adopting autonomous safety and security standards or selecting competent national market surveillance authorities are political and strategic decisions that must be carefully considered from a country-specific perspective, bearing in mind the consequences of the various available options.

I have also had the honour to be received by the Italian Ambassador in Armenia, H.E. Mr Alessandro Ferranti, and to find, in his words about the ongoing work of our Embassy in this country, the same focus on collaborating with and supporting Armenian institutions while respecting the specificity of this country. A beautiful and tangible example of this in action has been the recent restoration of the Garni mosaic, showcasing not only the bridge between two cultures, but also the possibility to continue a common path.